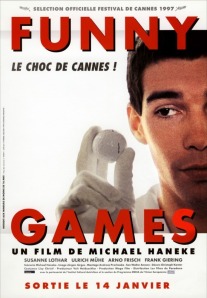

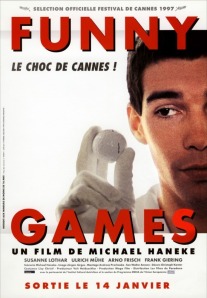

Artists working against the backdrop of modernity have been preoccupied with cruelty. The target of this cruelty is consistently displaced from artwork to artwork. In can be the artist himself as in Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971) a performance piece which saw Burden shot at close range in his upper arm by an assistant wielding a .22 calibre rifle. Cruelty can be directed towards an audience as in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) where the viewer’s desire for vicarious bloody violence is fulfilled, over-fulfilled and ultimately laughed at. A work of art can also be cruel with regards to its represented subject as Sade’s gleeful exploitation of his fantasies in a work such as Les 120 journées de Sodom (1785) or the seemingly offhand racism and misogyny of characters in Michel Houellebecq’s Les Particules élémentaires (1998) demonstrates.

Maggie Nelson’s long, thoughtful text is an intensely personal attempt to get to the bottom of, to fully understand what is at stake when we talk about cruelty. Her approach, scholarly but still immensely readable, is somewhat more sympathetic than her more reactionary forebears. Paul Virilio, for example, in La Procedure silence (2000) over-simplistically described the output of the contemporary art world into two mutually-exclusive hemispheres: “pitiless” art, concerned with cynically exploiting art’s capacity to shock, and “pitiful” which evokes a degree of compassion for its subjects. For Virilio, who cites the work of the Viennese Actionists and the Young British Artists as evidence of such “pitiless” cruelty, the majority of contemporary artistic output falls into the former category, which excludes any redemptive pity. Whilst the art she considers could fall into Virilio’s category of “pitiless”, Nelson’s approach is far subtler, taking what she sees as the full complexities of cruelty into consideration: it might not necessarily exclude the “pitiful”. This book is an attempt to get a deeper appreciation of cruelty as artistic method by not dismissing it offhand, but rather by working with it and evaluating the legitimacy of such an approach. Indeed, Nelson suggests that her real aim in The Art of Cruelty might not only to be getting to the bottom of cruelty at all, positing that her real goal may be to get a greater insight into compassion, cruelty’s “far enemy” (p. 8). In such a way, whilst Nelson’s aim is frequently to investigate the bloody, the offensive, even the appalling, her approach is characterised by a clear optimism, a consideration of where the value really lies within the artworks under consideration.

The “reckoning” of the book’s title is, then, less a conclusive settling of scores than a critical consideration from all possible angles. As Nelson is quick to admit, this highly subjective approach is not always productive; she doesn’t have all of the answers. This refreshing honesty lends a slightly elliptical edge to the text: by embracing the cruelty of the artworks she discusses Nelson isn’t always immediately able to suggest clear conclusions. Discussing the work of American artist William Pope.L, which frequently explores identity issues affecting black American males, Nelson admits, “[…] this says something. What on earth it says, I have no idea. I like it, though, because it bothers me, and I’m not sure why” (p. 204). Such inconclusive conclusions are not unequivocally a bad thing, and, whilst it could prove frustrating for readers looking for immediate answers, who might be better served by Virilio’s text, are certainly preferable to disingenuously forcing a critical position. The ambiguous response is, as The Art of Cruelty argues, a valid one.

Nelson’s overall stance is most coherently articulated in the closing pages of the text. Rather than looking to take sides for or against cruelty within art, Nelson proposes a third way: “[…], a practice of gentle aversion: the right to reject the offered choices, to demur, to turn away, to turn one’s attention to rarer and better things” (p. 269). In an age driven by snap media-fuelled judgements of a predominantly anti-intellectual mainstream where one is forced to assume a false position ‘for’ or ‘against’ art, arguing for the right to make an enlightened choice, to turn away, walk out, or close the book. Nelson’s approach is inspired by critic Roland Barthes’ late work on neutrality which proposes a less confrontational critical position. Nelson errs consistently on the side of thinking and making informed choices; filing the book on a high shelf rather than burning it, her text is thus an assertion of what she sees as the empowering potential of neutrality.

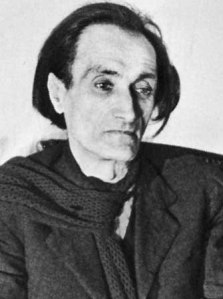

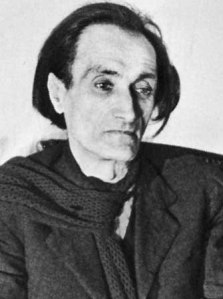

That’s not to say, however, that Nelson’s work is necessarily opposed to cruelty per se. Rather she seeks to provide a challenge to what she describes as of the dominant principles of the twentieth century avant-garde, the roots of which she traces to Antonin Artaud’s ‘theatre of cruelty’. Nelson’s target is the assumption, which she describes, recalling the military strategy of obliteration of the enemy as “shock and awe” art, that artistic cruelty is somehow a therapeutic response to the alienated subject in society. She challenges the notion that art, through shock or violence, has the capacity to provide the individual with access to a higher or transcendent truth. Nelson quotes Haneke’s memorable, if abhorrent, description of the process of “raping the viewer into independence” (p. 4). There are, for Nelson, different shades of cruelty, and the subtlety with which she reveals the spectrum of cruelty is the true value of this text. Nelson’s analysis seeks to articulate a use-value for cruelty, to ascertain when it can be truly artistic or valid approach and moves beyond the shock, the point Virilio’s analysis stops. She is sceptical of works that claim to reveal or impose truths, instead aligning herself with artworks that provide new ways of seeing or understanding the predicament of the contemporary subject. Through reference to the work of RD Laing she describes such art as “works that give clear pictures of these knots or binds, rather than those that hope to offer a map out of them” (p. 11). Acceptable cruelty for Nelson, whilst it may be intensely visceral, is primarily intellectually enlightening rather than cynical, mindless or idiotic. Nelson formulates it as art:

“[…] which dismantles, boycotts, ignores, destroys, takes liberties with, or at least pokes fun at the avant-garde’s long commitment to the idea that the shocks produced by cruelty and violence – be in in art or political action – might deliver us, through some never-proven miracle, to a more sensitive, perceptive, insightful, enlivened, collaborative, and just way of inhabiting the earth, and of relating to our fellow human beings” (p. 265)

This is at odds with the predominant culture of idiocy, or an “idiocracy”, “[…] in which low-grade pleasures (such as the capacity to buy cheap goods, pay low or no taxes, carry guns into Starbucks, and maintain the right not to help one another) displace all other forms of freedom, even those of the most transformative and profound variety” (p. 30) [Author’s italics]. Whilst Nelson’s text offers a study of the cultural field, there is much more at stake; her text consistently brushes with the societal implications of the observations she makes.

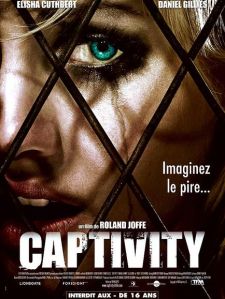

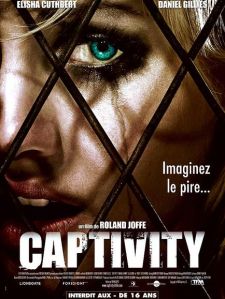

Nelson’s text is rich in its examples of artistic cruelty, both redeemable and otherwise. Her analysis, however, recognises that her examples can be viewed from either perspective. The visual work of Francis Bacon and the poems of Sylvia Plath are repeatedly explored and problematised, with Nelson, in both cases highlighting how the cruelty of their work has aspects which can be viewed in terms of both their brutal horror and the insight their work provides. As an example of idiot or purely thoughtless cruelty, Nelson posits cynical cinematic “torture porn” such as Roland Joffé’s fillm Captivity (2007).

One of Nelson’s most pertinent observations is the association she makes throughout the text between cruelty and clarity, citing Artaud, she asserts, “cruelty signifies rigor, implacable intention and decision, irreversible and absolute determination” (p. 6). Her cruelty is one that stimulates thought; whether the starting point takes the form of physical violence or presents its viewer with complex truths and provocative questions, articulated by Nelson as the “brutality of fact”. Indeed a consistent thread running through Nelson’s text is a consideration of the legitimacy of the apocryphal equating of kindness with cruelty. Redeemably cruel art is, for Nelson, that which, whilst it may contain a certain shock value, cuts through the superfluous, discovering, if not truth, then alternative discourses, or another side to what is presented as truth by dominant discourse. As an example from within society Nelson cites the activity of the Yes Men, an activist group which launches media hoaxes to draw attention to the duplicity of corporate discourse. In 2004, the group, claiming to be representatives of the Dow Chemical company, gave a BBC interview revealing a $12 billion compensation payout for the 120,000 victims of the Union Carbide pesticide gas leak in India. This duplicitous declaration forced the genuine Dow to publicly re-assert its position that it “still had no intention of helping the people of Bhopal, or of detoxifying their land” (p. 158). The chemical company branded the Yes Men’s stunt “cruel”, illustrating the true ambiguity of the world; where does the real cruelty lie? In the stunt or with the chemical company? Similarly, Plath’s poems, albeit on a more intensely personal level evoke a poetic brutality, she wields not only a “scimitar of clarity” (p. 262), but the “meticulously coiled internal rhymes and consonance” of her poems are described as razor blades (p. 218).

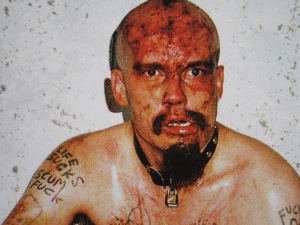

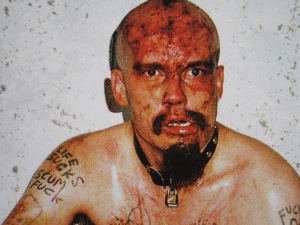

In Plath’s case of course, given her ultimate suicide, these blades also prefigure very real self-harm. This metaphor, the linking of the act of incision to perform a search for latent truths or nihilistically demonstrating the fact that no such truth exists, has itself been consistently reformulated in the work of transgressive visual artists. It is characteristic, for example of the work of Damien Hirst whose 1993 work Mother and Child Divided comprised a bisected cow and calf and placed in gallery vitrines filled with his trademark formaldehyde. It equally calls to mind the performances of musicians such as GG Allin and Iggy Pop, known for their on-stage self-mutilation, cutting themselves in front of an audience to heavy rock soundtracks. As her example, Nelson selects, the work in the 1960s of the Viennese Actionists whose films of their “actions” from the period feature: “[…] multiple forms of mutilation, beatings, penetrations and bloodletting” (p. 21), and whose later work such as “actionist” Hermann Nitsch’s Six-Day Play (1997) has continued this spirit but within the context of performed rituals designed to explore and even create the mythic.

This relationship between art and truth is particularly pressing for Nelson’s consideration of the links between art and extremity. Nelson makes a clear distinction between an older generation of artists, such as Nitsch, who seek to use ritualised transgression at the centre of their art as a way of exploring or uncovering truth, and a younger generation epitomised by tRyan Trecartin whose work, which all plays out within the hyperreality of his videos suggests, and even celebrates, the impossibility of transcending the media spectacle to find any such truth. Nelson’s response to the ‘canonical’ trangressors, such as the Actionists and their theoretical forebears Nietzsche and Bataille, is pleasingly iconoclastic, and is not adverse to ridicule; Bataille and Nietzsche are criticised for the implicit misogyny of their work, whilst the supposedly provocative work of the Actionists is frequently held up as pompous, mindlessly offensive or just worthy of being laughed at.

Indeed laughter is posited by Nelson as an important and, as she argues, a valid response to “shock and awe”. The pantomime qualities of Nitsch, Sade and Bacon’s work, their tendency, intentional or otherwise to provoke laughter, are repeatedly noted by Nelson. Laughter is for Nelson a legitimate response to extreme art, particularly when that art is po-faced and dictatorially performed in the name of enlightenment. Laughter as response, however, can naturally be misconstrued as dismissive or inappropriate as with the case, which generated a media-led furore and recounted here, of a group of adolescents who responded in that way during a screening of Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.

Legitimate laughter as opposed to mocking derision as a response to artistic extremity is a novel consideration, as is Nelson’s interest in the spaces around the video screens in an installation of Paul McCarthy’s gory and gloriously anarchic Caribbean Pirates (2001-2005) rather than the on-screen action. Nelson’s work is most interesting when it takes a similarly tangential or unorthodox approach to its object of study. The notion of brutal honesty, in the form of “right speech” (p. 155) is also a key component of Buddhist ethics and Nelson’s analytical position in The Art Of Cruelty is informed as was Barthes’ work by Eastern thought systems. Indeed, the metaphor of incision considered above can be extended through the Zen notion of swordsmanship (pp. 207-208). This is particularly relevant from the perspective of Mahayana Buddhism where, for example, the Bodhisattva Manjushri is often depicted with a flaming sword. Nelson notes: “[i]ts task is to keep slicing through all of the ways in which we attempt to hold onto a sense of solid ground, all the ways in which we resist the fundamental impermanence of all things” (p. 209). In a way, the Buddhist approach is in itself transgressive encouraging, as it does, a perspective which strives to allow the individual subject to cut through the superfluous within experience, to move beyond the discourses and desires generated by contemporary society to find neutral balance and in so doing discover the innate fluidity of truth, rather than higher or imposed truth. This is the same role that Nelson appears to cast for her artistic form of compassionate cruelty which gives an insight into man’s predicament, rather than forcing a solution. Transgressive Buddhism is just as violent to our notion of reality as the works of Bacon or Plath, but this violence differs in terms of its practicality, offering a direct possibility that our perception can be changed rather than offering an experience that remains within the cultural.

Nelson also makes a number of valuable ethical observations relating to complicity and the key role played by our consent with regards to extreme art; more specifically the consent a gallery goer, audience member or reader gives to be shocked by a piece of art. She observes, for example, that there is a fundamental difference between the way we respond to literature, where the mind is frequently fully imaginatively engaged in the production of a text’s effect, producing emotional feelings of guilt and collusion, whilst an ‘assault’, felt as a shock most frequently comes via an explicit visual image. There is additionally an undercurrent of politics to Nelson’s work, arguing that the contemporary US climate (Nelson is an American, writing in America) notably propagated by the foreign and domestic policies of the Bush administration can arguably be defined in terms of its cruelty.

Nelson’s exploration of cruelty also has implications for the role we expect art to play within society. For all of The Art of Cruelty’s insistence on art that crosses boundaries, the corpus of Nelson’s study, why it does on occasion refer to mainstream cinema and TV (such as the series 24), is broadly confined to the intellectual worlds of literature and art, which the vast majority of her examples are drawn from the world of so-called high art. Despite her compassionate intent, Nelson explicitly turns a blind eye to what she terms (p. 10) “stupid cruelty”, the targets of whom are arguably most eagerly in need of a compassionate response. “Stupid cruelty” for Nelson is “misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia [and] racist norms”. The sad fact is that “stupid” or ignorant cruelty is a dominant force within contemporary society, certainly more of a force than the redeemably cruel art that Nelson advocates in her book. The rise of social media has, for example, seen the regrettable rise of “trolling” with individuals deliberately looking to provoke or shock the sensibilities of others with upsetting Tweets or blog posts. Equally, the worldwide phenomenon of reality TV where candidates are subjected to humiliation after humiliation for the dubious honour of ‘celebrity’ and the monomaniacal outpourings of Fox News or the Daily Mail are symptoms of a world where cruelty is a particularly pressing issue. The Art of Cruelty is an impressive attempt to delve into the implications of a dominant artistic trend. A fully compassionate study of cruelty will, however, be one that gets to grips with, and perhaps offers a way out of the stranglehold it has throughout society.